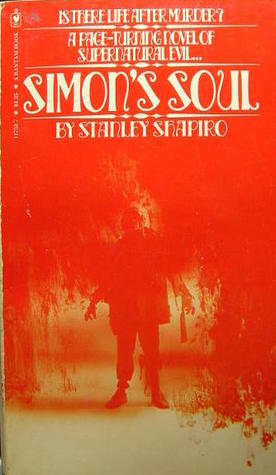

It took a while for me to realize that the things that scared me most were products of my imagination. That’s not to say I’ve never been scared by a movie or a book, obviously. But much of what’s really stuck with me through the years were products largely or sometimes solely of my mind. I forget exactly how young I was when I started praying for nightmare-free sleep before going to bed, but it should have been apparent to me then. And if not then, it should have been apparent around the time I first became aware of a relatively obscure novel titled Simon’s Soul.

It took a while for me to realize that the things that scared me most were products of my imagination. That’s not to say I’ve never been scared by a movie or a book, obviously. But much of what’s really stuck with me through the years were products largely or sometimes solely of my mind. I forget exactly how young I was when I started praying for nightmare-free sleep before going to bed, but it should have been apparent to me then. And if not then, it should have been apparent around the time I first became aware of a relatively obscure novel titled Simon’s Soul.

I can’t pinpoint the exact year for this little story, but I know it was no earlier than the summer of 1988, because June of ’88 is when the original Metal Gear video game was released in North America for the NES, and that’s the game I was playing when I first heard about Simon’s Soul. Accounting for the probability that my folks didn’t buy me a new game immediately after it came out, I can narrow the time frame down to being before the summer of 1990, because that’s when the movie Flatliners hit theaters; the relevance of this factoid will become apparent shortly. For the moment, let’s say that the following took place in the summer of 1989, which would put me at 9-years-old.

I was in the living room, sitting on the floor in front of the television, glued to the game, but aware of my mother and her friends behind me, sitting on the sofa and chairs, talking about things that didn’t really interest me. I figure my mom thought I was too focused on the game to pick up on anything she said; a reasonable presumption. I’m not exactly sure why my ears perked up when she started giving her friends a quick, enthusiastic summary of Stanley Shapiro’s novel.

Here is how I remember my mother describing the opening of the story (note that this is not meant as an accurate summary of the book, just a remembrance of someone else’s summation): a group of scientists decide to seek proof of the afterlife. To do so, they set up an experiment to actually kill one of their own, Simon, while hooking him up to a machine that allows him to convey his thoughts and experience back to the others during the process. At first he ventures into death with a sense of wonder and curiosity, but gradually his isolation breeds fear and dread. There’s nothing visible, audible or otherwise identifiable out there beyond death, so far as he can tell, but there is an existence nonetheless. Not quite nothingness, but also not actually anything. He asks his colleagues to bring him back, but they either can’t or, for the sake of science, won’t. Then, finally, he starts to sense something. Wherever Simon is, there’s a place beyond that, and he senses something living on that other-other-side is trying to break through the barrier to make its way to where he is. At that point he’s begging his colleagues to bring him back to life before whatever else is out there gets to him, and does heaven only knows what from there. And then…

Then the subject changed. I have no idea how the conversation got to that point, or how it changed. Maybe my mom cut it off there so as not to spoil the rest for her friends, in case they wanted to read the book. Or maybe a phone call came in and interrupted her. Maybe they all got up to leave for lunch and she continued the story out of earshot. Whatever the reason, she stopped her recap of the novel there, and though I was terrified to know what was going to happen next, I was more terrified to never find out. Leaving off there, with Simon stuck in that strange limbo, with some unknown thing trying to get at him from some place deeper in the hereafter, did one hell of a number on me.

Isolation is a key component to horror–something that didn’t really dawn on me until it was pointed out by my outstanding 11th & 12th grade English teacher, Mister Comer. Fear can make you feel pretty lonely. Many other emotions are more apt to be communal experiences. Happiness, anger, even grief. But fear–horror–even when it’s experienced in the midst of other people is still a very private emotion. Other emotions more easily lend themselves to empathy, I think. We can have a ceremony such as a funeral where everyone can gather to mourn and express their sadness. There are parties thrown for celebratory occassions, so everyone can get together to smile, dance and laugh. You can even have rallies built around anger, where everyone can unite around how fed up they are, and how they’re not going to stand for it anymore. But for someone else to truly understand and feel how horrified another person is, they have to be horrified themselves, which means each individual is very much dealing with their own shit. You don’t have rallies, parties or ceremonies where everyone gets together to share their fear. I mention all of this because I can’t think of anything more frightening and lonely than being stuck on the other side of death with no one else around, no sights to be seen, no sounds to be heard, and no way to get back from the void.

Again, I was about 9 or 10 years old when my mom accidentally dropped the Simon’s Soul synopsis on me, so I wasn’t giving deep thought to the loneliness of horror at that point. I just knew there was something about this fragment of a story that scared the hell out of me. Scared me so much, in fact, that I couldn’t play that damn Metal Gear game for several weeks afterward. In my mind, the game’s (otherwise charmingly goofy / “spy themed”) music was associated with what I knew of Simon’s Soul; a man’s spirit locked in the stark crawlspace between our world and an antagonistic afterlife. When the movie Flatliners hit theaters in 1990, I remember telling my friends that there was a book out there that had covered similar ground, but I couldn’t get any of them to understand how creepy it genuinely was. Again, I was alone with my fear on this.

Again, I was about 9 or 10 years old when my mom accidentally dropped the Simon’s Soul synopsis on me, so I wasn’t giving deep thought to the loneliness of horror at that point. I just knew there was something about this fragment of a story that scared the hell out of me. Scared me so much, in fact, that I couldn’t play that damn Metal Gear game for several weeks afterward. In my mind, the game’s (otherwise charmingly goofy / “spy themed”) music was associated with what I knew of Simon’s Soul; a man’s spirit locked in the stark crawlspace between our world and an antagonistic afterlife. When the movie Flatliners hit theaters in 1990, I remember telling my friends that there was a book out there that had covered similar ground, but I couldn’t get any of them to understand how creepy it genuinely was. Again, I was alone with my fear on this.

Cut to a little more than a decade later, and I would still think of Simon’s Soul on occasion, much more so out of curiosity by that point. I had just gotten comfortable with the idea of buying anything via the internet, and lo and behold, I soon discovered someone selling a used, hardback copy of the book online. Naturally, I decided to get it for my mom as for one of her birthday presents. It arrived and I couldn’t even wait for the actual occasion to give it to her. She appreciated the gesture and placed the book on the shelf, but it soon occurred to me that the book hadn’t been occupying space in her mind the way it had in mine. Not even close. For her it was just something she’d once read and recommended to friends. Besides that, she was by then a grandmother, and as it is with many people as they age and get a few grand-kids under their belt, her tastes in fiction had softened. Dark, relentless stories centered around a despairing, trapped soul didn’t much appeal anymore to the woman who had just started taking semi-annual road trips to Disney World with the family’s latest additions.

In a (very selfish) way, this was a win for me. I realized pretty soon that she wasn’t in any hurry at all to revisit the book. I didn’t have to wait for her to finish it, or even get started on it, before I could borrow it and plow through it. So I did. And…

…Well, in fairness, there was almost no way Simon’s Soul could have lived up to what I’d mentally prepared myself to venture into. The opening chapters of the book came pretty close to it, however, taking me through the journey into the dark hereafter that I’d so dreaded as a youngster. Thing is, I’d unreasonably presumed that this particular scene was what the entire book would focus on. So when it moved beyond that and into an increasingly imaginative and bizarre self-contained mythology involving demons amok, possession and an afterlife where Hell and Heaven exist, but souls don’t always end up where you think they should, for reasons not quite within the range of human understanding, I couldn’t help but feel disappointed. It’s still one hell of an intriguing, engaging horror novel, and it doesn’t pull punches. On first read it kind of reminded me of some of the Dean Koontz novels I’d read; how the story can end in a place so far afield from where it began you want to flip back to the first chapter to be sure you aren’t mis-remembering how the story started, but Shapiro’s story is ultimately darker than any of the handful of books I’ve read by Koontz.

In the end, I don’t know if I can fully recommend Simon’s Soul the novel. But the memory of it had an indelible impact on the kid with the near-masochistic fascination with the macabre and horrific.