I had my first and only real experience with a hurricane when I was barely six years old.

In 1985, two days after Labor Day, Hurricane Elena struck the Mississippi Gulf Coast near Biloxi. My family lived in Ocean Springs, less than five miles away, effectively putting us in the path of the storm.

Elena made an odd detour on its way to Mississippi, however. Odd enough to be responsible for what was, at the time, the largest peacetime evacuation in United States history.

After it ran up the length of Cuba and emerged in the Gulf of Mexico to strengthen, all the reputable meteorologists agreed that the likeliest landing spot for the storm was Biloxi, Mississippi. Although it wasn’t an exceptionally powerful storm, as a Category 3 it was still strong enough to encourage people to flee from it. As recommended, my family packed up and headed north, to Jackson, Mississippi, like many others, expecting that the storm would be a safer remnant of its former self by then.

I have vague memories of this. I can still see the pale walls of the motel room my parents booked. And I can remember not understanding why, after driving for a few hours to get out of the storm’s path, we headed back home before we could come close to settling in at the motel.

Hurricane Elena had made an abrupt turn East, and now was expected to smash into the Florida panhandle, sparing Mississippi (as well as its neighboring states) entirely. Before it reached Florida, however, it stalled out, waited a bit, then turned back West.

It could have then targeted Northeastern Florida, or Georgia, or Alabama, or gone further West into Louisiana, Texas, or even Mexico. Instead, it set its sights on the same place it had initially aimed for. Mississippi.

Consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Subscribed

To be fair, and much more accurate, the storm still impacted several of these other states, and it also didn’t consciously set its sights back on Biloxi, Ocean Springs, or anywhere else. Hurricanes do not have “eyes” in the sense that seeing things do, and certainly have no minds of their own. Other weather conditions influenced Hurricane Elena’s erratic path. These simple, obvious facts interfered a bit with the lore of the storm, however.

When I would hear the storm discussed later, over the years, or talk about it with my friends (hurricanes commonly cropped up in conversation in school since the most active period of hurricane season coincided with the start of the school year) Elena would be spoken of almost as though it were a thinking, spiteful being. Its behavior was also subject to casual exaggeration.

“Remember when Elena changed course two or three times before it hit?” someone might say. “You can never tell what these storms want to do.”

Hurricane Elena killed nine people, a number my horror-brain refuses to affix the word “only” to. Each of those who died endured their own horror story, and the same could be said for some the survivors, be they injured or unharmed. It’s important to remember that. But the fact that other storms have killed more people—and have also done more damage—is also important in certain contexts.

For instance, Elena’s relatively… let’s say “contained” death toll and destructiveness made it yet another storm subsumed by the larger lore of what is still the most powerful named hurricane to strike the contiguous United States.

Not the deadliest, not the largest, and not even the overall strongest. The unnamed Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 remains the most powerful. Several others have killed more people, chief among them the Galveston Hurrricane of 1900.

A storm with a name is given a certain, additional character, though. It is intrinsically personified. This is captured in the title of a U.S. Department of Agriculture documentary about the hurricane I am alluding to: A Lady Called Camille.

Elena had its own story, that of it boomeranging back to Mississippi as though it were deliberately trying to fake out the place it meant to strike all along. But it was still destined, like many others before it (Hurricane Frederic in ‘79, Ethel in 1980, Danny from earlier in ‘85), and after it (a different Danny in 1997), up until Hurricane Katrina, to be part of Camille’s story, in the sense that it could never measure up.

“Yeah, that storm was bad, but it wasn’t no Camille.”

“Camille was the big one.”

“There’ll never be another Camille.”

These aren’t exact quotes, but close approximations to things I overheard. Hell, I think I even said something along those lines while talking about powerful storms with my friends—even though Camille struck a decade before I was born—just so I could sound like I knew what I was talking about. Sound like the old-timers who seemed to know better. Though I hoped saying such a thing would make me stand out, it didn’t, because all of my friends were liable to say the same.

For instance, when Hurricane Gilbert, a Category 5 that would strike Mexico, stirred in the gulf, we all seemed to agree that even though meteorologists said it was on par in strength with Camille, and even larger than the legendary “lady” that slammed into Mississippi in 1969, Gilbert still couldn’t be Camille’s equal.

There’ll never be another Camille.

It took years for me to find out that certain stories about Camille were embellished, and that one, the big one, was an outright lie.

People would say that Camille sank Dauphin Island, for instance. Now, due to the way people pronounced it, I didn’t find out until years later that it was called Dauphin Island and not Dolphin Island. At the same time, I discovered that the island did not actually “sink.” Camille flooded about seventy percent of Dauphin Island. The water eventually receded however, and Camille was not the first storm to do this to the island.

Camille’s impact on Dauphin Island was absolutely destructive, but I don’t think it qualifies in any sense as a sinking. I think of sinking as physically depressing or drawing something underwater, as opposed to pushing water over top of it. When a flash flood inundates a city, for example, we don’t say the city sank.

People said Camille sank Dauphin Island, like it was a micro-Atlantis. I wonder if they were conflating its story with that Dog Key Island, home to a resort and casino known as the Isle of Caprice, which apparently was permanently submerged by a storm back in the Prohibition era. Either way, the claim that Camille sunk an entire island sounded perfectly believable to me back then.

After all, I had been through a storm that changed direction like it meant to evade a pursuer, and that one wasn’t even all that powerful compared to others. If Elena could weave, wind back, and trick its trackers, then why couldn’t Camille do something that sounded almost mythological?

I also heard people say that Camille “cut Ship Island in half,” and indeed there once was a West Ship Island and an East Ship Island, divided by a part of the gulf called the “Camille Cut.”

Ship Island has since been reunified thanks to a massive engineering project, but Camille was indeed responsible for its former separation. But I think the terminology I heard used is important to the lore of Camille. Saying that the storm divided the island into two was not quite enough. People said it cut the island in half.

That sounds a lot more deliberate, doesn’t it? It does to me. Like the storm had a goal, or was obeying fate. In truth, the two parts of Ship Island were not neatly halved. One side was fatter, the other thinner and longer. It looks more like a broken glaive (a comparison I doubt anyone I knew in Mississippi was going to make at the time); West Ship Island looks like the blade, East Ship island like the long handle.

It might not seem important to you, but had I seen an image of what West and East Ship Island looked like when I was young, I’d have been slightly underwhelmed. I would have expected the cut to have at least been closer to the classic magic trick of sawing an assistant in half, cut at the geographic equivalent of a waistband, if not at a point producing perfect symmetry.

Both of the previous examples could be categorized as exaggeration, or even misinterpretation on my part. Camille’s most famous bit of lore, however, is entirely false, despite being documented beyond oral tradition.

It is referenced in a 1974 television movie titled Hurricane. It is the centerpiece of an episode of the beloved sci-fi series Quantum Leap. It even shows up in the aforementioned U.S. Department of Agriculture documentary titled, “A Lady Called Camille.”

Nonetheless, the infamous “hurricane party” apparently never happened.

The story of the party is simple and, I dare say, almost classically mythological. Twenty-four residents of the Richelieu Apartments in Pass Christian, Mississippi, decided not to evacuate as the storm approached. In fact, disregarding the storm’s threat, they elected to hold a party, believing the storm’s threat to be overstated. Overblown, if you will. I could expand on that pun for a couple of sentences at least, but I’ll spare you that.

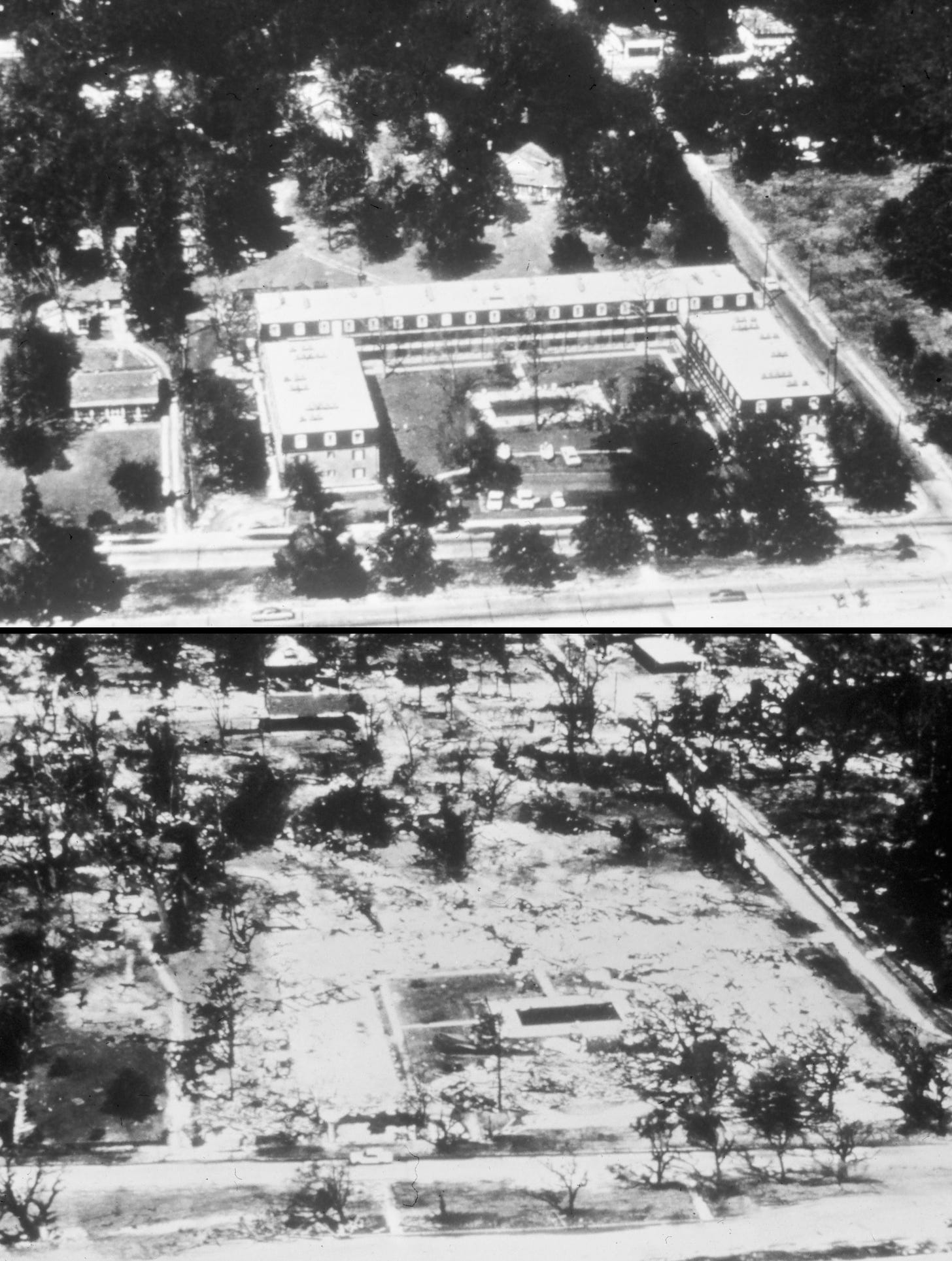

After the storm passed Pass Christian, the Richelieu Apartments were essentially no more. Camille had swept the entire, three-story apartment building off its foundation. Only one person from the party—and indeed the entire complex—survived to tell the tale.

It feels like a modern fable. Mortals flout their vulnerability before the might of forces bordering incomprehensible, and are wiped out save for one allowed to live on to give a warning to others. Even the name of the apartments—Richelieu—matches that of one of the most arrogant villains in literary history, Cardinal Richelieu from The Three Musketeers.

The elimination of the building is true.

The story of the party is false, as is the part about there being a lone survivor. Several people actually survived the annihilation of the Richelieu apartments, and there was no ridiculous celebration thrown by residents to taunt nature and the fates, according to said survivors. Now, you might be tempted to think they could be telling a self-serving version of events, not wanting to appear foolishly reckless when asked about what happened to them and why they chose to stay. The simple truth is, though we might hate to admit it, sometimes people just miscalculate and make a mistake that isn’t that uncommon to make. A mistake we or someone we care about could make. Other times, escaping an impending disaster is a luxury unavailable to certain people.

However, as survivor Josephine Duckworth reluctantly admitted, “I guess the hurricane party makes a good story.”

It does, its falsity notwithstanding.

The “hurricane party” rumor contributed something more fanciful, more appropriate to legends of man’s arrogance and downfall, than did more verifiable accounts and evidence of Camille’s impact.

The measurables, for instance: winds clocked at 179mph; a 24-foot storm surge (for reference, here’s a video of a 15-foot storm surge from Hurricane Ian); 259 human lives lost.

The photos of ships beached, boats deposited in neighborhoods, images of buildings swept away or flattened.

The small, almost idyllic community on Deer Island, which had survived previous hurricanes, electing not to rebuild after Camille’s devastation.

These things certainly built the legend up, but the idea of Camille felt incomplete without the stories. Many of the houses that withstood the storm became legends themselves, because by God, if they could survive Camille what couldn’t they survive? An asteroid impact? A nuclear bomb? Godzilla? A house that couldn’t be killed by Camille couldn’t be killed by anything, some people believed.

Human beings are storytellers, and most of us are at least a little bit interested in capital-H Horror, whether we realize it or not. Camille was a Horror story without a proper villain, if you adhered to logic, and didn’t adjoin the word “super” to the word “natural.”

So some people made the storm—her—into a living, thinking villain, whether or not they were conscious of it.

Camille sank Dauphin Island.

She cut Ship Island in half.

She knew about those partiers in the Richelieu Apartments and made an example out of them.

She wasn’t the first of her kind to be offended to the point of becoming violent at such defiance, either. I mentioned the flooding of Dog Key Island, aka The Isle of Caprice, earlier. Legend has it that revelers at the resort and casino on the island ignored attempts to evacuate them ahead of a hurricane as well, and they were all washed out into the sea, never to be seen again.

That storm—or, perhaps, a series of storms—that struck the Isle of Caprice, however, lacked a proper name. Naming something can be important to ascribing villainy. Think of the shark in movie Jaws, which many people simply call “Jaws,” as though that’s what its mother called it. That helps to transform it from just being a shark into being something evil.

Likewise, from the way I remember people speaking of her, Camille wasn’t just a hurricane, she was a monster.

I still wonder exactly how much of Camille’s mythology contributed to Hurricane Katrina’s death toll in Mississippi. While most people understandably associate Katrina with New Orleans, due to its abysmal impact there, it actually made landfall nearer to Biloxi, and killed at least 238 Mississippians. I recall reading accounts—who knows how true—of old-timers choosing not to evacuate with Katrina looming, deciding they could endure because they lived in one of those heroic homes that had withstood Camille, and Katrina, as it made landfall, was technically a “weaker” storm.

It was, unfortunately, also far larger, and far slower. Camille was a compact, speeding demon, Katrina a lumbering beast. Camille was stronger, but threw its hardest punches and then hurried on like it was expected elsewhere. Massive Katrina lingered; its size and slowness made it deadlier.

According to local newscaster Walt Grayson, the mayor of one of the Mississippi Gulf Coast’s towns once said, “Camille killed more people in 2005 than it did in 1969 when it hit,” because so many people still saw Camille as the ultimate—“the big one”—so how bad could Katrina be?

Camille’s lore was arguably even more powerful than the storm itself.

Incidentally, you might be wondering, “Who was that mayor that Walt Grayson spoke of?” Walt says during the broadcast that he can’t remember who it was. So maybe he actually heard it, or maybe he’s misremembering, or perhaps embellishing. How fitting.

I share all of this here because I do feel the impact of Elena and the specter of Camille affected my affection for—and youthful belief in—the frighteningly supernatural. That may seem like a tenuous connection to make, but my obsession with disasters—be they man-made or, especially, natural—has always run second only to my fascination with horror and ghost stories. I look at my bookshelves, physical and digital, and amidst the horror fiction I also have books about The Johnstown Flood. The sinking of the Princess Sophia. The Great Lisbon Earthquake. Dozens more. Isaac’s Storm and A Night to Remember are right at home with the likes of The Only Good Indians and Hell House in my library. I’ve never seen a tornado in person, yet have had more nightmares about massive twisters than almost anything else, save for xenomorphs.

So, for me, these different types of horrors have always been somewhat comingled. I fell in love with ghost stories only about a year before my experience with Elena, after all, and I first started hearing about Camille almost immediately after that. That somehow made it easy for me to believe that the “Rock & Roll Graveyard” in Ocean Springs was indeed haunted, and also the site of Satanic sacrifices, as people alleged. It was easy for me to believe that “Old Biloxi Hospital” was full of ghosts as well. That one of my friends from school lived on a street where a parade of ghosts from a circus—animals included—marched at midnight, as he claimed. That another friend’s deceased grandmother haunted his home, and they could tell because sometimes they’d smell freshly baked apple pies—her specialty—when they returned to their empty house after dining out, or going to a baseball game, or what have you.

I could even believe something as ludicrous as Bloody Mary living in a dilapidated house behind a restaurant near my neighborhood. That’s what a classmate named David told me. He also told me Mary was abnormally tall, almost a giant, and missing a finger because a gator had bitten it off.

Absurd, yet why couldn’t it be true? Why not, when nature itself could be so bizarre? So malicious? So actively villainous?

Storms could bisect islands like maniacal surgeons. Sink other islands like an angry god. Punish prideful and imprudent partygoers with death.

The natural world seemed supernatural to me, back then.

Everything was believable. Anything could exist.